A season and an era ended in Pasadena, and to be there is to welcome the feeling.

To get to the end of the BCS, and to the title game and the end of the 2014 football season, college football had to first squeeze its surly, disorganized self through the eye of the Rose Bowl.

To do this, it had to get through the stadium's tunnels, guarded by men and women holding placards reading THIS TUNNEL IS FULL PLEASE WAIT. There is a "please" there: you should know how polite the Rose Bowl is. You should know exactly how many security guards and other newly deputized warm bodies moving in the name of public order there are. Your parking pass is checked five separate times on the way into the stadium. Your bags are checked twice, and thoroughly, by people who do respectable rummaging.

Getting to the press box requires a passage through four different inspections of your laminated press pass and one electronic scan of the badge. This is done by smiling, polite people in jackets who are everywhere. They stand in matched pairs by the escalators, eying badges, medallions, and the various cardboard permissions dangling around the necks of passersby.

Getting into the Rose Bowl requires a slow digestion through the bowels of officialdom, but getting to the Rose Bowl only requires that you ransack a golf course. Pasadena is a beautiful place where nothing is supposed to happen, and yet here they were. Florida State bros in fitted caps and Jameis Winston jerseys split a 12-pack of Bud Platinum on the edge of a water hazard. Men in orange Auburn fishing shirts stomped through the margins of the bunkers, parked their trucks and rental cars on the cart paths, and set up camp along the shaggy edges of trampled fairways.

For some reason, some parents brought sun-blasted, snoozy, face-painted children along. They were asleep on shoulders or drowsing with bare legs jutting out from strollers and rammed through crowds of circling fans, all eddying around the shape of the Rose Bowl.

The Rose Bowl can be finicky, but most of that persnicketiness is obliterated by the thing itself: the trees on the edge of the stands, the San Gabriel Mountains behind them, and the shock blue of the sky streaked with wispy cirrus clouds blown to bits by winds flying off the Pacific Coast.

From the eye of the cameras mounted in the press box, it is a perfectly composed postcard trampled by a football game. From the field cameras, every shot is framed by the curve of the stadium and bathed in the bright, velvety light of Los Angeles, which is a very real and persistently beautiful thing.

You don't want to believe it, but it is annoyingly true. A vulture in a tracksuit could take a handsome portrait in the stands of the Rose Bowl.

So if from a certain point of view, from a certain spot on a third turn around the stadium, staring at little more than the impossibly beautiful shade of blue of the sky, you got a little ... overwhelmed? By the moment, or the fragility of the moment, or maybe just from sleep deprivation and the way the sunlight died a little, how it gave way to darkness shot through by the blazing crackle of the stadium lights? That you were there, trying to be critical, when suddenly you got the urge to take your shoes off and just walk barefoot for a minute on the turf?

It would happen there, with a shit-eating grin on your face. You would be thinking the very silly thought that if you were to die here, in 68 degrees and with the promise of a football game to come, that would not be the worst thing in the world.

You would have missed certain things by dying before the game.

You would have missed Auburn taking the field and obliterating any pretense of a blowout in the first half, knocking a frantic Winston out of sync by using disguised coverages and harrying Florida State into a flat spin to start the game. The Seminoles blew things they hadn't blown all year. They abandoned the run in a panic. They forced Winston to spray the ball like a malfunctioning sprinkler to receivers who, after a full year of catching everything thrown to them, developed an allergy to completions.

You would have missed Gus Malzahn on a playcalling streak of such ferocity that even his mistakes looked like the outline of sinister design. At one point, after a Nick Marshall pass that landed incomplete 10 yards from his receiver, I leaned over and said, "That's not what he wanted to do on that play." The man next to me said, "Nah, even that's setting something up." That's how far into Florida State's head Malzahn was at one point: he was gaslighting the Seminoles into rapid onset derangement with a quarterback who had been a defensive back at Georgia two years earlier. His team was throttling the Heisman Trophy winner with a defense that nearly lost a game to Washington State to start the year.

You would have missed the moment when Gus Malzahn took the SEC's worst team not named Kentucky and almost won a national championship.

You also would have missed the FSU band doing a James Bond halftime show and playing "Skyfall." You would have missed hearing the opening words in your head: Thiiiiiiiiiis is the end.

For years leading up to 2013, Florida State was back, then suddenly was not. A horde of four- and five-star recruits became three-star teams capable of implosion against the most random competition: NC State, Virginia, and other lesser denizens of the ACC. The Seminoles played as a menagerie of incendiary talents occasionally guest-starring as a unified squad, and at other times simply loitering as individuals in televised random pursuit of a football.

This was the end. Levonte "Kermit" Whitfield returned a kick, and words are inadequate, because words do not really describe how gone Whitfield was at his own eight-yard line. Geometries collapsed, pursuit angles melted, and Whitfield was in the open. He was fleet, untouched, and blistering toward the end zone.

I once watched a F-14 over a golf course in Destin, Florida hit the afterburners early, break the sound barrier over land, and scream out to the Gulf of Mexico on a vector of pure reckless glee. That was Kermit Whitfield's kickoff return.

The end is where the math piles up in every sense. For Auburn, the math meant running so many plays that Tre Mason would eventually slip a tackle and bound into the endzone with 1:19 on the clock. Mason, falling forward and over defenders, riding the rolling wave of his own tumbling linemen, and scooting under tacklers all night, finally broke a long run at the best of all possible moments for Auburn.

In other words: a 2013 Auburn thing happened, again.

The end, though, also meant the tallying of sums for FSU. The recruiting of speed, pure, terrifying speed like Rashad Greene, who slipped through a hole in the Auburn secondary for 47 yards. An offensive line that in 2011 allowed 41 sacks and had given up four on the night held Auburn at bay for one long drive. The end was a well-scouted hole in the Auburn goal line defense: between the hashes, three yards deep into the endzone. Goalpost-sized human Kelvin Benjamin found a Jameis Winston pass 10 feet or so above the grass in that spot.

The end arrived. Numbers were tallied. After four years of building to this moment, Florida State had reached critical mass some time in the fourth quarter of the final BCS Championship. It achieved full escape velocity at the last and best possible moment.

If something as big as Benjamin made a sound coming down with the game-winning touchdown made a sound, I didn't hear it. A camera truck barreled its way around the corner of that end zone, the same end zone Vince Young ran into for the winning score in the 2006 BCS Championship against USC. Security guards in yellow windbreakers herded reporters, cameramen, randoms, and VIPs into a thin margin of turf along the sideline.

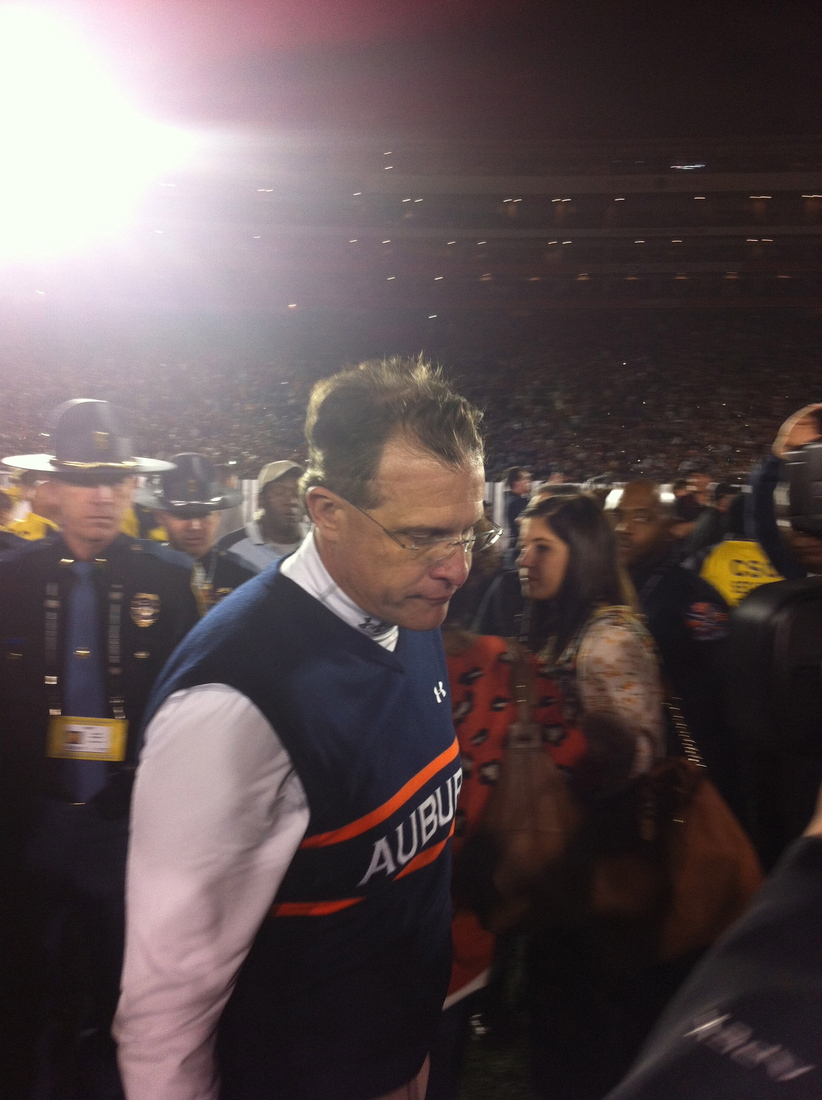

Cheers exploded behind me from the FSU section. Something like a loud silence dropped from the Auburn sections, a kind of noise-canceling atmospheric sorrow you sometimes hear and simultaneously don't hear when something very, very unfortunate happens to a mass of football fans. It is a sucking of wind into the lungs, a collective extended gasp.

![]() Must Reads

Must Reads ![]()

A crew of extremely uncertain security people cordoned off the middle of the field with a rope. A confetti gun appeared. It belched flakes of garnet and gold plastic into the air. Large, young men made festive trash angels in the middle of the field. A boy in an Auburn jersey lingered on the sidelines, crying so hard his mother, bent double over him and wiping with her shirt, couldn't keep up with the tears. I thought about taking a picture, but my hands wouldn't move. They had a conscience of their own.

James Wilder Jr. led the marching band. "We are the Champions" played. I walked back up to street level. I passed one Florida State fan, looking tranquil and slightly dazed. He looked at a friend, and said this in a deliberate, level voice:

"We are gonna go to jail together tonight."

![]() More from our team sites

More from our team sites ![]()

A continent of garbage is floating in the Pacific Ocean. Plastic bottles, bags, aerosol cans, six-pack rings, and other assorted plastic meso-litter swirls in a current called the North Pacific Gyre. It is hard to tell exactly how big it is. It might cover eight percent of the ocean, but it might be a fraction of that, a mere drop of swirling trash in the immensity of the ocean.

It's out there, though, one big swirling metaphor for everything wrong with college football. This is an end, but only for an acronym and the attendant business arrangement associated with it. Courts could shift the winds in a second, bringing everything crashing to shore in a single wave of long-delayed reckoning. Players could shift the currents themselves. Schools might reform before reform is forced on them, beginning the cleanup all on their own.

Nothing at all could happen. Nothing happening is always an option when dealing with enormous messes.

The sun set over the hills behind the Rose Bowl last night just after kickoff. It tracked west as the earth rolled away from it, and drew shadows across the face of the pressbox. High clouds blowing towards the mountains fluoresced with the sunset. The sun dove still lower before disappearing into a reddened, garbage-strewn Pacific 40 miles or so to the west. The stadium lights obliterated the stars from the sky, and then all you could see was the game.

More from SB Nation college football:

Follow @SBNationCFBFollow @SBNRecruiting

• Plot twists and the ends: Bill Connelly on the Championship’s numbers

• Florida State: The SEC’s worst nightmare

• How FSU and Auburn were built: Why recruiting matters so much

• College football news | Final Top 25 led by FSU, Auburn, Michigan State