Spencer Hall interviews former SR-71 Blackbird pilot Rick McCrary about what it's like to fly the world's fastest plane. Spoiler: It's terrifying.

SH: How did you end up flying that thing?

RM: Well, I'd be lying if I said there wasn't a lot of luck involved. I entered the Air Force in 1970, and was accepted for pilot training. After I completed that, I was a pilot instructor for about five years in the T-38, the supersonic trainer the Air Force still uses to this day. Subsequent to that I flew the F/B-11, the Aardvark, up at Pease AFB, New Hampshire. Then I was actually on nuke alert up there when I got a phone call from a fella I flew T-38s with who asked if I was interested in "a new position." I was due to rotate, so I said sure.

I was anticipating a desk job, which is just part of the rotation cycle as an Air Force officer. I can't say I was looking forward to it. He said that he'd been out with the SR-71 program, and that they were looking for a pilot. Of course, that was an easy answer. They said, "Well, why don't you come out and have a look," so when I got off alert that tour I flew out to Sacramento and drove up to Beale AFB to meet everyone.

SH: So you couldn't even fly into the base?

RM: No, only the planes stationed there could--the SR-71, the KC-135 refueling planes, etc. I got up there on a Saturday, and caught up with them a little bit, and then they said, "Well, let's go look at the bird." They were all in small hangars, all closed. We unlocked the back doors, turned on the lights, and I thought "Oh lord, there's a spaceship."

SH: And that was the first time you saw it?

RM: I'd never seen the airplane before, so it was just awe-inspiring. It's so unique compared to other aircraft, just that flat black plane. It really was a sight.

SH: Are we in "breathtaking" territory here?

RM: Yeah, it just took your breath away because it was so different looking. The shapes are very different depending on what perspective you have walking around the aircraft. But nowhere did it look like anything flying to this day.

SH: What was its reputation among other pilots?

RM: Very little was known about it by anyone else. It was still sight-sensitive. You could see it, but you couldn't walk up and touch it, or look at the cockpit, things like that. It was never out for public display. It would fly missions and always taxi right into the hangar. It flew sensitive reconnaissance missions, so very few people knew anything about it outside the community. I only knew what was in the public record, as well.

To see the size of it was just...awesome. Until you see it, you really don't have a feel for how big it is for a fighter-type aircraft: 107 feet long is a big airplane. Because of the black color, it has this massive look to it, with those giant engines out there on the wing. Again, just an incredible sight, and unlike anything else I'd ever seen before. I was hooked at that point.

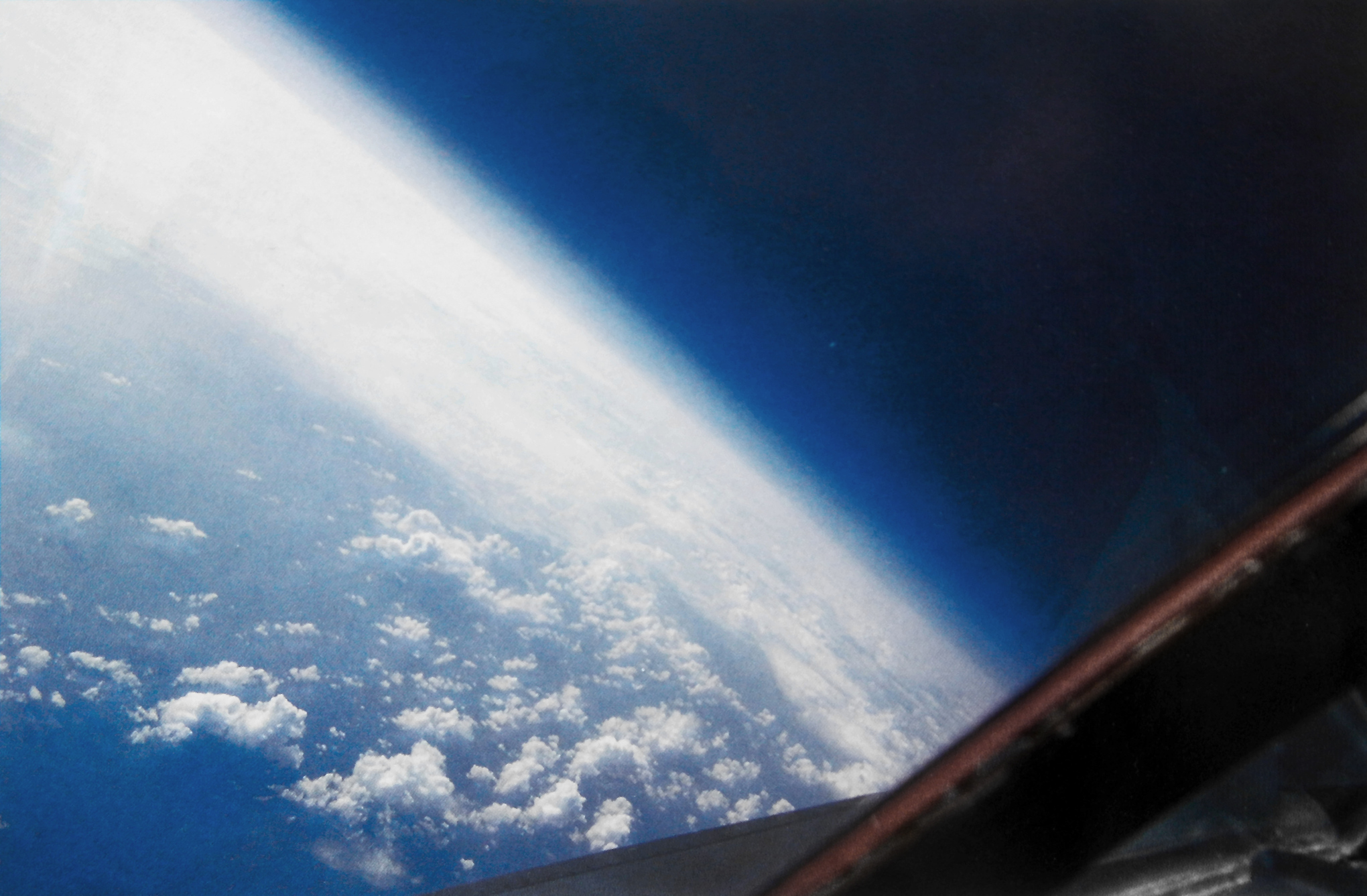

Photo credit: WikiCommons

I then met several of the other crew members, and that began a courtship, if you will. They had a very small crew force at the time, less than ten pilots and less than ten reconnaissance system operators (RSOs). At any time, about a third would be deployed, a third would be training or on vacation, and a third would be doing operations from their home base. Seldom did you have many people around.

SH: Is that odd to have such a small crew? Out in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of high desert California, isolated from the rest of the world?

RM: It truly was. The only other people there were like us: the U-2 people and their crews, our tanker crews, and us. It was a very self-contained operation with a small group of people who couldn't talk about what they did when they were away from there. There really was very little open information about it even in the Air Force at that time.

You really had to get to know each other pretty well. It largely was a social check, a compatibility check to make sure that you could get along with the crew. You spent more time with your crew than you did with your family, since once you were training you'd spend fifty percent of your time on the road deployed on missions, and fifty percent you'd be home training locally. There were certifications and a lot of stuff, too, but the first visit was mostly to see if you got along with everyone.

SH: Were they looking for a specific kind of person?

RM: Yes but there were qualifications, first. You had to have flown two high-performance aircraft. You had to have had an in-air refueling background, and you had to have a perfect flight record without any medical issues at all. That all happened before you got there. But having a friend who had flown with you really helped, because only then did they make the call. They didn't use the normal personnel system. It was really a personal recommendation for a person who could pass the screens and the social check.

After I passed the social check, it was about "are you serious about doing this," and that there was a lot of impact on the family. Believe it or not, it could also be a career limiting thing, because it broke your normal way up through the Air Force career system by not taking the desk job at that point.

Once I saw the plane, though, I couldn't have cared less about that. I'd wanted to be a pilot since I was six years old, and to me this was as good as it was ever gonna get.

SH: When you do that kind of training, they don't just throw you in the cockpit, right? How does that work?

RM: You go back to your normal duty, then they set up an astronaut physical. That was an all day thing, with brain scans and treadmills and all that kind of stuff. They get recommendation letters from your bosses, all that. Then I went back for the formal interview, which included flying the T-38--which we flew as a kind of companion trainer, since the SR-71 was so expensive to operate.

You got in the SR-71 simulators, which was your first real look at what the plane could do. They interviewed everyone you knew, and then six weeks later I got a call telling me I was accepted. Once we relocated out there, I started into an academic study to understand the airplane. They do that for any plane you fly, because you need to understand all the systems of the plane, all the performance characteristics, all of that so that if you ever have an emergency you know what to look for. There was a lot of study, including going down to Burbank to meet Kelly Johnson, the famous engineer who designed the aircraft, and Ben Rich, the chief designer of the inlet system--which is the real magic on the airplane.

They crewed you up. There were two people to a plane: a pilot, and a reconnaissance systems operator. He had to have that same operating background that you did. (My backseater had flown F-4s and F-111s.) You were set for four years together, which is important because of the way the plane was. There were two seats, fore and aft, with no visibility between. There was a titanium bulkhead between you and the backseat.

SH: Like, literally a wall?

RM: Literally, a wall. You have no visual, so you have to communicate over the intercom. After a while, you learn to anticipate each other just from the tenor in the voice, that kind of thing. We had simulators all the time, we'd fly in the trainer just to learn to work with each other. We did six months of that until we got comfortable with the systems, and understood the basic airmanship of the aircraft.

Then we did four flights with an instructor pilot. Normally you'd get quite a few more than that with any other airplane, but again, this was such a special machine, and cost so much to operate, that that's why they hired people who could transition into a plane quickly and who already knew how to refuel in mid-air.

The trainer had two pilot stations, so the backseat occupant could see forward. It could be flown from the front seat, or from the backseat, but really the instructor was there to serve as a navigator and make sure everything was going okay. My first flight, I had the same instructor who'd taken me through the grueling simulator training, and there were no surprises. It was just like the simulator except for the raw experience of sitting inside an aircraft of that power and immensity. You had to get used to the spacesuit, too.

SH: People forget you had to basically wear a space suit.

RM: It was a Gemini suit, built for sitting. Very cumbersome. It was the same suit you'd see astronauts walking into the capsule in, except ours were gold.

SH: How long did that take to put on?

RM: We'd go in about four hours before flight. Each day they'd give you a mini-physical, since you couldn't fly in a space suit with a head cold or anything like that. We had a backup crew ready for each mission ready to substitute. You'd then go have a breakfast, what was termed a "high-protein, low-residue meal" of steak and eggs. You're gonna be trapped in that suit for six or eight hours, the low-residue part is pretty important.

SH: This is the other really practical question here: it's a space suit, so you're diapered up, yes?

RM: That was an option. You did have a tube on, what looked like a big condom. It had a nipple on the end of it, hooked up to a tube that led down to a bag with sponges in it. Those little hard sponges you see somewhere that when you put water on it, it expands to its real size? That's what was in these things. That's what you used for urination. The plan was to never use anything else. If you did, you just did.

They did have a diaper for extremely long flights, but I don't remember anyone ever using it. For one thing, if you were not well you did not fly. Everyone trained hard, everyone was in great shape, you watched what you ate. You used that little bag, and that was quite a challenge. You had to get the differential pressure right or you'd be sitting in wet pants for the whole flight.

Also, half the crew that suited you and de-suited you were female. You had a great working relationship with them. You just hated to come back it with poop in your pants. There's a lot of stuff in the job that isn't in the shiny brochure.

SH: Going back to another detail: was there any other plane where you had to go back and meet the dude who made it? That seems unique to me.

RM: It was very unique, but it was a very unique program and airplane. It stayed a very small community to the end, and that included the manufacturer, the operators, and the systems people. We had Lockheed technicians with us for every flight. If you had an issue, you could talk to them. There were small teams of people with you whenever you deployed overseas, and were always there for technical advice. It was a small club.

SH: Your tech support for the Blackbird was 24/7, and always there, in other words?

RM: Absolutely.

SH: What was it like when you finally got to fly it for the first time?

RM: You waddle out there in your spacesuit, carrying your little cooler because it gets quite hot in that spacesuit. You go out to a van with some La-Z-Boys in it, these big recliners, and they drive you out to the airplane. It's sitting there with all the cables hooked up to it, just like a space launch. It's outgassing stuff, people are checking it, and then people start unhooking it and leaving and then it's just you and the crew chief.

You get into the seat, close the hatch, and you're in your cocoon. Startup was also a unique thing. It had this special fuel, because the temperatures during flight got up to over 600 degrees Fahrenheit when you're at speed. The worry is that normal fuel, which you want to explode quickly during flight and have a low flashpoint, well...you wanted the exact opposite with the Blackbird. You're carrying so much fuel that the last thing you want to worry about is it self-igniting.

SH: Because the whole plane itself is already well above that flashpoint, and the whole thing would explode, right?

RM: Yup. That's gonna be a bad day.

SH: This is kind of a theme with the Blackbird, right? That the physics you're normally working with are all totally different because of the speed?

RM: Right. Everything is different. In that first six months of training, they had to break all your habits you had from your first ten years of flying. It's just different, and you can't react to things that would normally happen the way you would in other planes. It was a vector, not a line.

They had this special chemical ignition they stored in a little fuel tank the size of a grapefruit that has this wicked chemical in it, triethylborane. It explodes when it comes into contact with oxygen. The way you get this engine going--because it was so massive-- was this special starting thing with two 454 cubic inch V8s and a gear drive that they would just jack up into the bottom of the airplane. And when you said go, they'd redline those Buicks and the big motor would start to turn over. You'd advance the throttle, give it the gas, and at a certain RPM you'd click the throttle over and it would let in this triethyborane that lit the fuel. It shot a big green flame out about 50 feet behind the airplane.

SH: So if I'm understanding the whole startup process is kind of like this space age Model T, where you cranked it just to get the engine up to speed?

RM: Yeah. It's just amazing, and points out a hallmark of the Skunk Works. Don't waste energy on something you have a solution for. You've got a lot of things to worry about already: how to keep the glass from melting at speed, how to keep the engines running at high speeds for long periods, how do you keep the fuel from exploding. If someone had a simple solution to something, then that's what they did. A very unique, very pragmatic approach. It was also part of the mystique of the thing, this fifty foot green flame shooting out from each engine on startup.

When you took off you were the only thing moving on that base. It was so expensive to operate that they took no chances with it. You took off five minutes after the fuel tanker and half full on gas, and didn't even get to altitude before immediately refueling. You burned fuel at such a ferocious rate in that plane.

SH: How fast were you burning through fuel?

RM: You'd burn 80,000 pounds of fuel in about an hour and twenty minutes. That's a lot of gas. You're on the boom a lot, and that was why in-flight refueling experience was such a critical part of the screening process. You didn't have a lot of time to do it, and you had to get it right the first time. Three refuelings was common, but on longer missions you'd refuel six or eight times. Those were long days.

You'd light up the afterburner right after that first refueling, and take it to full power for the next hour. That's pretty amazing, because no other plane can fly in full afterburner continuously. All other planes have either a three minute limit, or five minute limit on that, but you'd be going at full afterburner for an hour, hour and a half.

SH: Oh my god.

RM: It is an amazing machine. You start to climb up through Mach 1, and it's a big punch with a lot of air resistance. What we'd typically do is climb up, put the nose down just before Mach 1, and then lift back up and punch through it all the way to Mach 3.

SH: And this whole time, the pilot just wasn't on the gas and stick: you were actually changing the shape of the engine itself in order to get more thrust out of the engine.

RM: That's right. Because the faster you went, the more ram thrust you got, which burns less fuel. So you did have to go faster to burn less fuel. Like I said, you had to unlearn everything you knew about other aircraft.

SH: At that speed, things had to look so small, and pass by like stop signs, right?

RM: It looked like a relief map you had in school. That's what earth looks like to you from up there, that's the perspective you had. It's gorgeous.

SH: What was the most spectacular thing you passed?

RM: There were a couple of times. One of the most amazing sights was flying out of England to the north of Russia to have a look at things up there. If you did that, it was a pretty long run. We'd refuel twice just to get up there. You would get a couple of sunsets and sunrises, because at those northern latitudes often you would see day to night, and then a terminator line, almost like a black velvet curtain where you can see how it's light on this side, and dark on the other side. It's the most amazing thing you can imagine to see that.

Another one was at night. It's astonishing--you're above the haze, and in the atmosphere--how deep into space you can see from up there. There's all this meteor activity you never see on the ground. A lot of stuff's going on.

We flew across a huge thunderstorm that covered half of Montana. Looking down into it from 75,000 feet and seeing lightning going for hundreds of miles across the top of this giant storm was just awe-inspiring. Sometimes it was hard to pull your attention back into the cockpit because it was just mesmerizing to see that stuff.

Once we were coming down off the coast of California and letting down across San Francisco and hit this huge thunderstorm. We had to go down into it because we didn't have enough gas to go anywhere else. There was incredible turbulence as you penetrated the thunderstorm, and the aircraft is just bouncing viciously around. St. Elmo's Fire is just rolling across the canopy. It was kind of like the first scene in the original Alien. To get down, pop out the other side, and see our tanker waiting with gas was an incredible sight.

Every flight had something like that to remember.

SH: And part of the job is knowing your brain isn't prepared to handle that, and doing your job anyway.

RM: Yes. Because when things go wrong at that speed, they go wrong in a hurry. You can't overreact. That was the whole point of our training, to weed that out, because everything's going so fast that if you overreact you could put yourself into a position you couldn't recover from.

SH: And you're doing this for eight hours sometimes, which had to be mentally exhausting.

RM: Oh, you were just drained when you were done, and you weren't done until you were done. Landing was a challenge, as well. You didn't have good visibility with a very small window, high angle of attack when landing, and then trying to get it down at a reasonable speed. That aircraft had big chines around the airplane that block out your view of the ground. You had to just look to the side and go by sight. Once it got to the ground, you popped the big chute, and that was the last thing you were looking for. Your crew buddies would meet you at the bottom of the ladder with a beer.

SH: Beer for everybody afterwards?

RM: Yup. Then you'd debrief for an hour or more, not just about the mission, but about the plane. You have to remember that these were all hand-built, so you had to go through things with the other pilots and engineers like "I had this happen, and it's not in the checklist." Then another pilot would say, "I saw something like that before," and go back and try to correlate it. You were all working on it together, and there were no secrets. You'd say "I screwed this up" to everyone in order to grow the knowledge base.

SH: What was your schedule?

RM: You'd deploy for six weeks, and then be home for six weeks. You'd go to Japan, then come home, then you'd go to England for six weeks, and back and forth. While deployed, you'd fly twice a week or once depending on where you were. At home, you'd fly once a month just for proficiency's sake. You'd fly the T-38 every day and go into the simulator three times a week. You didn't fly the SR often, though, because of the expense. Almost every flight was operational, which is unusual.

SH: Other pilots who flew the SR-71 did not describe the plane as "fun." What was it like for you?

RM: You had a feeling for the mass of the airplane, even when you were on the ground. During the climbout you could always really feel it, so it was a great pilot's airplane. It's got a stick in it, just like a fighter does. You were always sitting on the front edge of your seat, just waiting for the next surprise. You're maneuvering things, you're moving fuel around, you're doing everything to optimize it and get as much speed and fuel as you can. That's something you love to do as a pilot, to be able to counter something and move through it.

Flying it when it was subsonic? It was actually a pretty honest airplane. You had a lot of power and light weight when you were low on fuel and ready to land. It was a thrill to fly. When you pushed those throttles up, it would just run away from you, and you had to stay in control. A good-handling jet. Like I said, it had limited visibility, but you could yank it, bank it, pull it around, and bring it in for a nice smooth landing.

When you were supersonic, you were just in a vector sitting on the pointy edge of it trying to maintain control. It was solid, reliable, and we had a lot of confidence in it. You knew it was going to bring you back. I had a couple of fires, but I had a lot of respect for the engineers.

SH: What was the diciest moment for you in the plane?

RM: I had an incident heading north out of England. We had just had a refueling point off the coast of Norway, and it was in January so it was dark almost all day. I climbed up to 72,000 feet in our second climb and had an engine fire. We shut it down, turned around, and started dumping all that fuel for an emergency landing at our assigned spot in Norway. (We did all of this planning ahead of time for where we'd land in an emergency.)

Well, they said that base was closed for weather. Now we had to scramble for another base. We found one that was close that turned out to be a snowpacked runway at night. We had a bit of anxiety going in there, as you could imagine. The airplane had never been landed under those conditions, but that was the case with a lot of things that happened to that airplane. We got it down and landed on the snow, and I had no idea how it would respond, but the chute slowed it down just fine and we pulled into the hangar. These Norwegian Air Force guys had basically seen a spaceship land in their field.

The commanding officer came to us and asked "What do you need?" I told him, "A telephone and a beer." I called the embassy, we had to repair it at the field, and two days later it was back in England.

SH: But just so I didn't miss the most important point: you landed an SR-71 with one engine on snow safely.

RM: Yeah.

SH: Did you know when your last flight was happening?

RM: The answer is kind of an interesting yes and no. There came the time to move on, and we had a good deal. We got to take it to the National Air Show in Washington, DC and put it on display there. That was going to be our last flight.

As we took off from there and came back around for a pass, the right engine exploded. We had to dump gas, and set about thirteen acres of Maryland on fire as we did that. That was kind of interesting, just spewing flaming fuel and titanium pieces around.

SH: This was rural Maryland, right?

RM: No, no, actually we were pointed at the White House out of Andrews Air Force Base. It was funny listening back to the voice tape because I start by saying "Well, we'll go out over the bay here and dump this fuel." About thirty seconds later I say "Screw it" and just dump it. We defoliated southern Maryland, but we got it back on the ground, which was great. After all that happened, I absolutely remember shutting it down. My legs started shaking uncontrollably with the adrenaline from it all when I knew it was over with. My co-pilot never flew again, either.

I had to have another qualification flight after the accident review as part of the process, though, so it turned out to not be my last flight

SH: Would you say that you miss it?

RM: No. It was special, but I knew the day I was done. I remember sitting in the La-Z-Boy in the van on the runway waiting to get in the plane and thinking, "I'm not as excited as I should be to be doing this." I flew the mission, went in, talked to the squadron commander, and then went to my staff job. I've never looked back.

It was an honor and a privilege, and I loved being a pilot, but what's left after that? I was done.